In response to news about construction of Virginia, Gideon Welles decided the Union would need an ironclad. Welles proposed to Congress a board of experts on ironclad ships. He was granted the authority to create this board a month later.

The Ironclad Board was composed of three senior naval officers: Commodore Hiram Paulding, Commodore Joseph Smith, and Commander Charles Davis. Welles put advertisements in Northern newspapers asking people to submit their designs for ironclads. The board initially chose two designs from the 17 submitted. These ships were the USS Galena and the USS New Ironsides.

Cornelius Bushnell, the designer of Galena, went to New York City to have his design reviewed by Ericsson. Ericsson, after assuring Bushnell Galena would be stable, revealed the plans and a cardboard model of one of his own designs, the future Monitor. Bushnell immediately knew Ericsson's ship was far superior to his own and pressed the reluctant Ericsson to submit the design to the Ironclad Board. Bushnell eventually obtained permission to take Ericsson's model to Washington. Directly after his meeting with Ericsson, Bushnell showed the design to Welles, who arranged a meeting for Bushnell with the Ironclad Board. History was made after that.

When the Commonwealth of Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, one of the important federal military bases threatened was Gosport Navy Yard (now Norfolk Naval Shipyard) in Portsmouth, Virginia. Accordingly, the order was sent to destroy the base rather than allow it to fall into Confederate hands. Unfortunately for the Union, the execution of these orders was bungled on April 20. The steam frigate USS Merrimack sank in shallow water before she completely burned. When the Confederate government took possession of the yard, the base commander, Flag Officer French Forrest, contracted on May 18 to salvage the wreck of the Merrimack. This was completed by May 30, and she was moved into the shipyard's only graving dock, where the burned structures were removed.

The wreck was surveyed and her lower hull and machinery were undamaged, so she was selected for conversion into an ironclad by Stephen Mallory, Secretary of the Navy, as she was the only large ship with intact engines available to the Confederacy in the Chesapeake Bay area. Preliminary sketch designs were submitted by Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke and John L. Porter, each of whom envisaged the ship as a casemate ironclad. Brooke's design showed the ends of the ship as submerged and was selected, although detailed design work would be done by Porter, as he was a trained naval constructor. Porter had overall responsibility for the conversion, but Brooke was responsible for her iron plate and armament, while William P. Williamson, Chief Engineer of the Navy, was responsible for the ship's machinery.

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on March 8, 1862, when Virginia engaged the blockading Union fleet. Despite an all-out effort to complete her, the new ironclad still had workmen on board when she sailed into Hampton Roads with her flotilla of five support ships Raleigh and Beaufort, Patrick Henry, Jamestown, and Teaser.

The first Union ship engaged, the all-wood and sail-powered USS Cumberland, was sunk after a furious cannon exchange, after which she was rammed in her forward starboard bow by Virginia. As Cumberland began to sink, Virginia's iron ram was broken off, causing a bow leak. Seeing what had happened to Cumberland, the captain of USS Congress ordered his frigate into shallower water, where she soon grounded. Congress and Virginia traded cannon fire for an hour, after which the badly-damaged Congress finally surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of Congress were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on Virginia. Outraged at such a breach of war protocol, in retaliation Virginia's captain, Commodore Franklin Buchanan, gave the order to open fire with hot-shot on the surrendered Congress, setting her ablaze; the frigate burned for many hours, well into the night, a symbol of Confederate naval power and a costly wake-up call for the all-wood Union blockading squadron.

Virginia did not emerge from the battle unscathed, however. Her bow leaking from the loss of her ram, shot from Cumberland, Congress, and the shore-based Union batteries had riddled her smokestack, reducing her already slow speed. Two of her heavy cannon were put out of commission, and a number of her armor plates had been loosened. Both of Virginia's 22-foot (6.7 m) cutters had been shot away, as had both of her upper-deck anti-boarding howitzers and most of the deck stanchions and railings. Even so, the now injured Buchanan ordered an attack on USS Minnesota, which had run aground on a sandbar trying to escape Virginia. However, because of the ironclad's 22-foot (6.7 m) draft, she was unable to get close enough to the grounded frigate to do any significant damage. It being late in the day, Virginia retired from the conflict with the expectation of returning the next day and completing the destruction of the remaining Union blockaders.

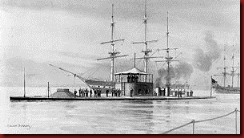

Later that night, USS Monitor arrived at Union-held Fort Monroe. She had been rushed to Hampton Roads, still not quite complete, all the way from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, in hopes of defending the force of wooden ships and preventing "the rebel monster" from further threatening the Union's blockading fleet and nearby cities, like Washington, D.C. While being towed south, she almost foundered twice in heavy storms on the way to Hampton Roads. She still had workmen aboard when she arrived by the bright firelight from the still-burning triumph of Virginia's first day of handiwork.

The next day, on March 9, 1862, the world's first battle between ironclads took place. The smaller, nimbler, and faster Monitor was able to outmaneuver the larger, slower Virginia, but neither ship proved able to do any severe damage to the other, despite numerous shell hits by both combatants, many fired at virtually point-blank range. Monitor had a much lower freeboard and only its single rotating turret and forward pilothouse sitting above her deck, and thus was much harder to hit with Virginia's heavy cannon. After hours of shell exchanges, Monitor finally retreated into shallower water after a direct shell hit to her armored pilothouse forced her away from the conflict to assess the damage. The captain of the Monitor, Lieutenant John L. Worden, had taken a direct gunpowder explosion to his face and eyes, blinding him, while looking through the pilothouse's narrow, horizontal viewing slits. The Monitor remained in the shallows, but it already being late in the day Virginia steamed for her home port, the battle ending in a draw without a clear victor: The captain of Virginia that day, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones, received advice from his pilots to depart over the sandbar toward Norfolk until the next day. Lieutenant Jones wanted to continue the fight, but the pilots emphasized that the Virginia had "nearly three miles to run to the bar" and that she could not remain and "take the ground on a falling tide." To prevent running aground, Lieutenant Jones reluctantly moved the ironclad back toward port. The Virginia retired to the Gosport Naval Yard at Portsmouth, Virginia, and remained in drydock for repairs until April 4, 1862.

In the following month, the crew of the Virginia were unsuccessful in their attempts to break the Union blockade. The blockade had been bolstered by the hastily ram-fitted SS Vanderbilt, and SS Illinois as well as the SS Arago and USS Minnesota, which had been repaired. The Virginia made several sorties back over to Hampton Roads hoping to draw Monitor into battle. Monitor, however, was under strict orders not to re-engage; the two combatants would never battle again.

On April 11, the Confederate Navy sent Lieutenant Joseph Nicholson Barney in command of the side-paddle CSS Jamestown, along with the Virginia and five other ships in full view of the Union squadron, enticing them to fight. When it became clear that the US Navy ships were unwilling to fight, the CS Navy squadron moved in and captured three merchant ships, the brigs Marcus and Sabout and the schooner Catherine T. Dix. Their flags were then hoisted "Union-side down" to further taunt the Union Navy into a fight, as they were towed back to Norfolk, with the help of the CSS Raleigh.

By late April the new Union ironclads USRC E. A. Stevens and USS Galena had also joined the blockade. On May 8, 1862, Virginia and the James River Squadron ventured out when the Union ships began shelling the Confederate fortifications near Norfolk; but the Union ships retired under the shore batteries on the north side of the James River and on Rip Raps island.

On May 10, 1862, advancing Union troops occupied Norfolk. Since Virginia was a steam-powered battery and not an ocean-going cruiser, she was not seaworthy enough to enter the Atlantic, even if she were able to pass the Union blockade. Virginia was also unable to retreat further up the James River due to her deep 22-foot (6.7 m) draft. In an attempt to reduce her draft, supplies and coal were dumped overboard, even though this exposed the ironclad's unarmored lower hull, but was still not enough to reduce her draft. Without a home port and no place to go, Virginia's new captain, flag officer Josiah Tattnall, reluctantly ordered her destruction in order to keep her from being captured. This task fell to Lieutenant Jones, the last man to leave Virginia after all of her guns had been safely removed and carried to the Confederate Marine Corps base and fortifications at Drewry's Bluff. Early on the morning of May 11, 1862, off Craney Island, fire and powder trails reached her magazine and she was destroyed by a great explosion. Her thirteen-star Stars and Bars battle ensign was saved from destruction and today resides in the collection of the Chicago Historical Society, minus three of its original stars.

Monitor was lost on December 31 of the same year, when the vessel was swamped by high waves in a violent storm while under tow by the tug USS Rhode Island off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Some of her crew went down with the ironclad, but many others were saved by lifeboats sent from Rhode Island.

No comments:

Post a Comment